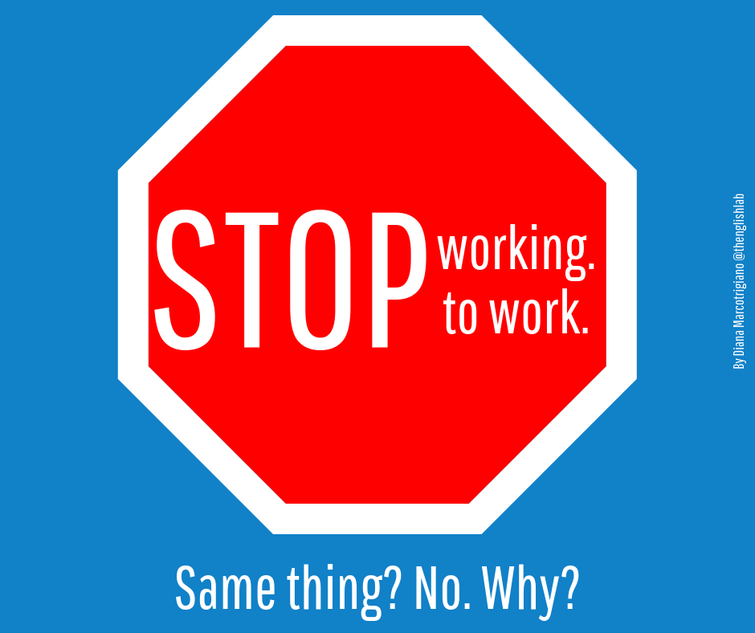

The stop sign in this image has two sentences, each with two verbs in a single clause:

Stop working.

Stop to work.

The relationship between the two verbs in the same clause is closely knit both in grammar and in meaning; the two adjacent verbs form what is called a verb pattern. In the case of 'stop' the meaning changes. Please read on to know how.

A verb patterns is just that—a pattern, a predictable recurrence. The predictability in verb patterns stems from the first verb. The form of the verb that follows from this first verb may be an -ing, like in ‘enjoy dancing’ and ‘love eating’; a to-infinitive, like in ‘refuse to talk’ and ‘manage to wake up’; or a bare infinitive, like in ‘help pack’ and ‘let be’. The first verb is also the one you conjugate; this means it changes to show tense, modality, and number. For example, look at how the verb ‘like’ changes and how the verb ‘sleep’ doesn’t in the following:

1. I like to sleep.

2. She likes to sleep.

3. He liked to sleep.

4. He must like to sleep.

Above, the verb ‘like’ is conjugated, thus is finite. The second verb, however, is non-finite, so it takes a form which is not conjugated, those being infinitives and participles. Note in example number 4 how ‘like’ is a bare infinitive when used after modals creating two non-finite forms in one verb pattern!

There are many patterns to follow in making grammatically correct sentences. Your compentency here will determine your level on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). For this post I will not describe all possible combinations, but I will just look at four categories of patterns that you should be able to use correctly at B2 level—and at this level you should know these patterns for a wide range of verbs. The four patterns are (a) the ones which only take an -ing, (b) the ones which only take a to-infinitive, (c) those which take both with very little difference in meaning, and (d) those which take both but with a change in meaning.

(a) So, there are verbs that are only followed by an -ing. Below are three of them in action—remember there are more than three!

They avoided eating vegetables when they were kids. (*avoided to eat)

We will finish renovating the house at the end of the year. (*will finish to renovate)

Corrupt politicians deny taking bribes. (*deny to take)

*Error

(b) Next, let’s see three of the many verbs that take only a to-infinitive:

She really did wish to come to the movies, but she was to busy. (*did wish coming)

Don’t hesitate to call me if you need any help. (*hesitate calling)

If you will agree to sell your house at a lower price, I will write you out a cheque today. (*will agree selling)

(c) Then there are those verbs which can be followed by either -ing or to-infinitive with very little change in meaning:

I began teaching as a young adult.

I began to teach as a young adult.

The potatoes would have started to bake already had you switched on the oven!

The potatoes would have started baking already had you switched on the oven!

It would be a good idea to continue to study over the summer break.

It would be a good idea to continue studying over the summer break.

Note that you can’t use an -ing if the first verb is also using -ing to form a progressive tense. Compare these:

She was beginning to teach kindergarten when the school was closed for two weeks due to a blizzard.

*She was beginning teaching kindergarten when the school was closed for two weeks due to a blizzard.

(d) Finally, the fourth point: the answer to the question at the beginning of this post. Here the choice between one form or another does make a difference in meaning:

1. Stop working.

2. Stop to work.

As a guide into seeing the difference in meaning, answer these question:

In which sentence is the action of working interrupted?

In which sentence is the action of working the reason for interrupting another activity?

When stop is followed by an -ing, it answers the question ‘what stopped?’ This shows you that ‘working’ stopped, so ‘working’ was the interrupted action.

When stop is followed by a to-infinitive, it answers the question ‘why?’ This shows that ‘to work’ is the reason for stopping.

Try asking yourself the same questions with these other examples here:

1. I really think you should stop thinking about it, or you’ll stress out.

2. She was so glad she had stopped to think before accepting the job offer.

3. When I get tired, I’ll stop cleaning up and take a break.

4. I think I’d better stop to clean up, or the mess will become more than I can handle.

5. Hey, you guys, stop chatting, and get on with the job, or we’ll never get this work done before the end of the day!

6. I bumped into my old high school buddy the other day, and we stopped to chat.

Be careful! The differences in meaning outlined above for the pattern with ‘stop’ should not be taken as a formula for understanding the different meanings between other verbs patterns that change in sense. Let’s take a look at another two, 'remember' and 'try', from this category:

I remember taking out the rubbish.

The action of taking happens before the action of remembering: you want to say that you have a memory of walking outside with the rubbish.

I remembered to take out the rubbish.

The action of remembering happens before the other action: you want to say that you know that you remembered because the rubbish is outside and who else could have done it!

Everyone was in a panic because the door was locked and nobody had a key. So, I tried opening the locked door with my hairpin.

The action of opening is a test to see if that action will work: you want to say you experimented.

The meeting was finally over! I grabbed my briefcase, and I tried to open the door. The door wouldn’t open. It was locked.

The action of opening was an attempt, not an experiment: you want to say that opening the door was your goal.

If you are an ESL student, I can only imagine how overwhelming lists of grammar rules can be for you. Native speakers of any language just know when to use one form instead of others. A native English speaker who hasn’t studied English grammar may read this post and have a deeper appreciation of the mechanics of English syntax. Nonetheless, being a native speaker does not automatically mean a person has an awareness of all structures at a level which allows them to give detailed explanations, so even a native speaker needs to check and revise—I do.

My tip? ESL students should not despair because learners do come to recognise good combinations from bad ones after engaging with the structures many times in many contexts. So my advice to everyone, regardless of your level of proficiency, is to have a lot of contact with the language in various forms (e.g. watching movies and reading magazine articles) and to always use a good dictionary—one that shows you which patterns a verb can take and the meanings of each pattern. The online dictionary I use most is Cambridge Dictionary.

Is there a particular pattern you would like me to break down?

Request a free 20-second takeaway. Please contact me. I will post one for you.