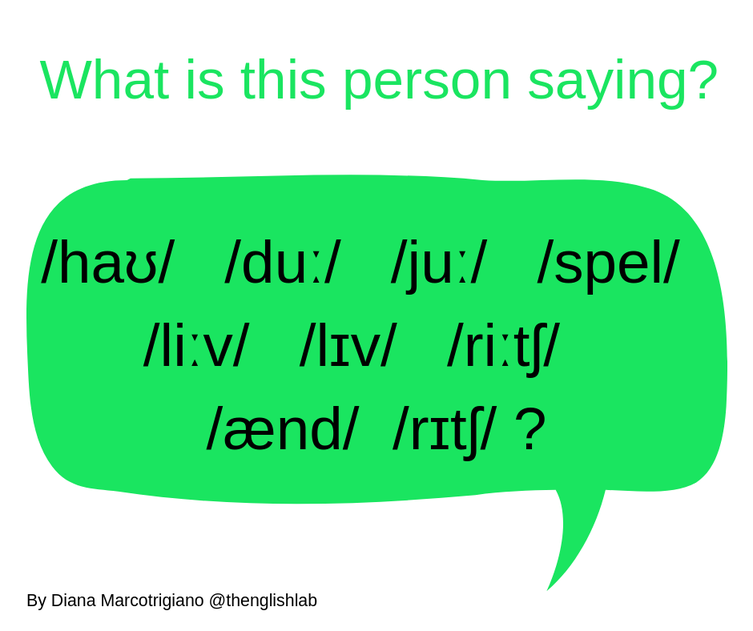

Leave, live, reach, and rich—how do you pronounce these words?

To begin with, the letters 'a', 'e', 'i', 'o', and 'u' do not represent five sounds, not in English anyway. None of these five letters in English has a one-to-one correspondence to a single sound. These letters represent a myriad of vowel sounds, and what is represented by the letter ‘i’, for instance, may be one of many vowels sounds depending on the word it is in. It is also important to underline that not only is there not a one-to-one correspondence of letters to vowels, but also the number of vowel sounds in English are significantly more than five.

In this post I will give examples from BBC English, otherwise called received pronunciation (RP). I am not advocating that one form of English is better than another; I’m just using one of the forms most used in English as a second language (ESL) classrooms despite my first love which is Australian English. I do appreciate hearing other English regionalisms such as the Scottish, Irish, north American, New Zealand, and other world Englishes. All good.

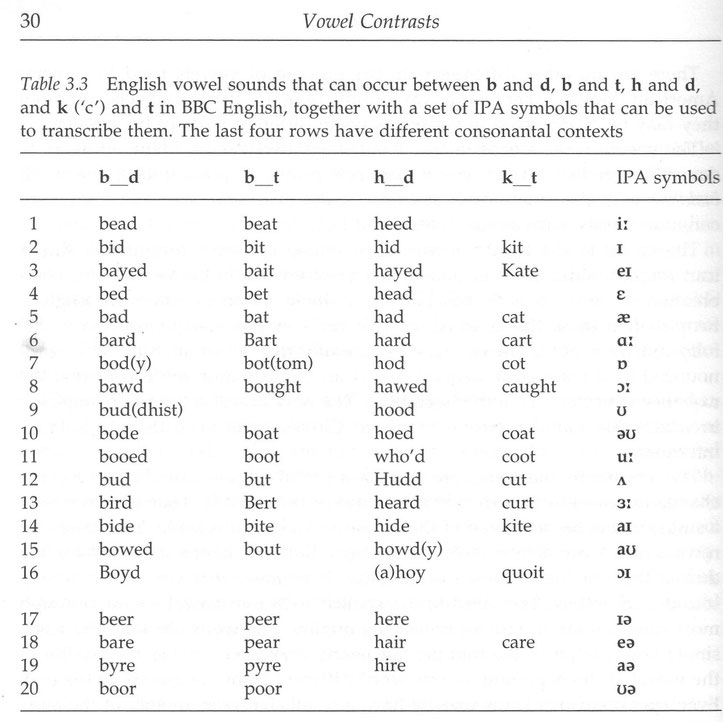

Nonetheless, BBC English has up to 20 distinct vowel sounds; this is more than General American English which has up to 15. In any case, English has more vowel sounds than many languages, more than Spanish, Japanese, * and Italian.†

All sounds that we can make for speech are represented by phonetic symbols from the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Here is a table to show you all the English vowel sounds represented by phonetic symbols, each within a word. Every column from numbers 1 to 16 shows how the sounds are contrastive for English:‡

Your native language (or L1) is going to influence your acquisition of a second language (or L2). Regarding L2 phonological acquisition (learning how to understand and produce the sounds of an L2), problematic sounds could be because they are not part of your L1. For example, the sounds /ɪ/ and /iː/ from the image of this post can be problematic for ESL learners if in their L1 these sounds are considered variations of the same sounds (allophones), hence not contrastive.

Native speakers (NS) of Italian, for example, need to learn to perceive and produce more vowels than they need for Italian when they are acquiring proficiency in English. So, two sounds which do not make a distinction in meaning in a learner’s L1 will be perceived as the same sound, collapsing into the same category: /ɪ/ and /iː/ à /i/. § A practical example is when a NS of Italian will most likely perceive and produce /bɪn/ (bin) and /biːn/ (been) both as /bin/, like an amalgamation of the two.

The first step to minimise this L1 interference is to recognise the differences in production features between the sounds: the shape of your mouth, the duration of the sound, and the muscular effort to produce these sounds. I will explain more further along in this post.

The second step is to show you that the meaning of words changes. So, you take two words that are almost identical because they differ in only one sound. If you pronounce the word with one of the two contrastive sounds, it means one thing; if you pronounce it with the other sound, the word has another meaning—these words are called minimal pairs. Just look back at the words in the image for this post and the table above and you’ll get a better idea.

Why is it important to understand the qualities and contrastiveness of /ɪ/ and /iː/? If you believe that these sounds are the same and that they do not create different words, you won’t hear them as different; here, your lack of hearing is not due to a hearing impairment, but a cognitive strategy. In other words your mind thinks the differences between the sounds are irrelevant because in your L1 they are irrelevant, so your brain does not register this as important, and you do not hear it. If your awareness does not change, you will continue to associated both sounds with one sound from your L1, and consequently you will not pronounce them well either.¶

Further down, I will give you a list of minimal pairs to show you that it is indeed important to distinguish /ɪ/ from /iː/. You will also be able to get some practice to improve your awareness of /ɪ/ and /iː/. If you’d like other examples of minimal pairs with other contrastive sounds, please read my post on /ð/ and /d/.

Now let’s go back to looking at how to produce /ɪ/ and /iː/.

What is going on in your mouth?

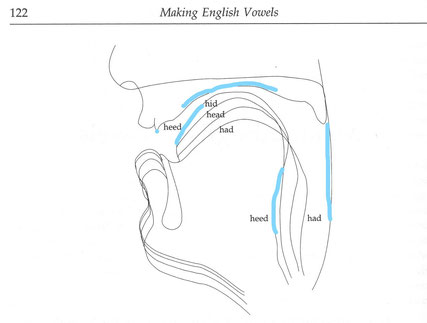

To produce /iː/, the tongue is pulled forward; there is a large space at the back of the mouth and, consequently, a small space between the teeth and the tongue. So, the tongue is high up in your mouth and forward near (but not touching) the back of your teeth. This is called a high front vowel. Take a look at the figure with the blue highlights here on the left. **

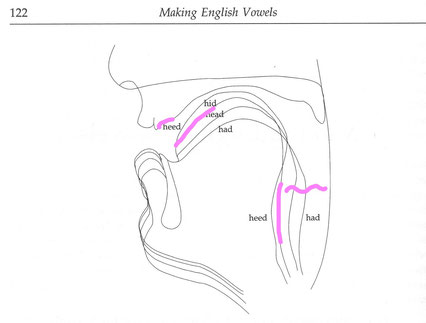

Next, to produce /ɪ/, the tongue isn’t as pulled forward as /iː/, so there is less space at the back of the mouth in comparison; the space behind the teeth is slightly more than the space needed to produce /iː/. You can compare yourself by looking at the figure with pink highlights here on your right.††There may be a slight drop in the jaw from the position held for /iː/, but the sound can be produced correctly even without the drop. This is called a mid-high front vowel.

In addition to the position of the tongue, there’s a difference in duration. One of the sounds is longer. The longer duration of vowel sounds in IPA is represented by a two-point diacritic placed immediately next to the symbol. It looks like a colon. So, /iː/ is a long sound, longer than the Italian /i/. It is possible to extend the length of this sound because /i/ is a tense sound in that there is more muscular effort to produce it compared to producing /ɪ/. By contrast, /ɪ/ is lax, not tense, and stays short. Tense vowels are higher (tongue position in mouth) and less central than their lax counterparts.‡‡ In fact, if you compare the position of the tongue of these two sounds, you will notice that /iː/ is higher. Compare again the figures above with the blue and pink highlights.

Getting back to meaning, as mentioned a little earlier, in English these two sounds are contrastive. Therefore, /bɪd/ and /biːd/have two distinct meanings: bid and bead; this is called a minimal pair.

Not being able to hear the difference between two contrastive sounds may mean that an L2 learner of the language concerned will have difficulty in recognising one word from another and will not be able to pronounce them properly either. Furthermore, what you perceive may not be what you actual produce. This can lead to communication breakdown.§§

Let’s now reduce communication breakdown by increasing awareness and practising:

1. Look at the minimal pairs in the table below; note their difference in vowel quality and meaning. If you don’t know the meaning of any words, I encourage you to look them up to learn them and be further convinced that you need to produce these vowels well. When you are ready, listen to the recording, pause between each pair, and repeat out loud. Do this as many times as you please.

|

minimal pairs |

||||

|

iː |

||||

|

Spelling |

Pronunciation |

Spelling |

Pronunciation |

|

|

/bɪd/ |

bead |

/biːd/ |

||

|

/bɪn/ |

bean or been |

/biːn/ |

||

|

bit |

/bɪt/ |

beat or beet |

/biːt/ |

|

|

bitch |

/bɪtʃ/ |

beach |

/biːtʃ/ |

|

|

chick |

/tʃɪk/ |

cheek |

/tʃiːk/ |

|

|

chip |

/tʃɪp/ |

cheap or cheep |

/tʃiːp/ |

|

|

did |

/dɪd/ |

deed |

/diːd/ |

|

|

fill |

/fɪl/ |

feel |

/fiːl/ |

|

|

fit |

/fɪt/ |

feet |

/fiːt/ |

|

|

gin |

/dʒɪn/ |

Jean |

/dʒiːn/ |

|

|

grin |

/ɡrɪn/ |

green |

/ɡriːn/ |

|

|

hid |

/hɪd/ |

heed |

/hiːd/ |

|

|

hill |

/hɪl/ |

heal or heel |

/hiːl/ |

|

|

his |

/hɪz/ |

he’s |

/hiːz/ |

|

|

hit |

/hɪt/ |

heat |

/hiːt/ |

|

|

is |

/ɪz/ |

ease |

/iːz/ |

|

|

it |

/ɪt/ |

eat |

/iːt/ |

|

|

lick |

/lɪk/ |

leak or leek |

/liːk/ |

|

|

live |

/lɪv/ |

/liːv/ |

||

|

pick |

/pɪk/ |

peak or peek |

/piːk/ |

|

|

pill |

/pɪl/ |

peel |

/piːl/ |

|

|

pit |

/pɪt/ |

Pete |

/piːt/ |

|

|

pitch |

/pɪtʃ/ |

peach |

/piːtʃ/ |

|

|

rich |

/rɪtʃ/ |

reach |

/riːtʃ/ |

|

|

ship |

/ʃɪp/ |

sheep |

/ʃiːp/ |

|

|

sill |

/sɪl/ |

seal |

/siːl/ |

|

|

sit |

/sɪt/ |

seat |

/siːt/ |

|

|

slip |

/slɪp/ |

sleep |

/sliːp/ |

|

|

still |

/stɪl/ |

steal or steel |

/stiːl/ |

|

|

Tim |

/tɪm/ |

Team or teem |

/tiːm/ |

|

|

wick |

/wɪk/ |

weak or week |

||

2. Now, read these out loud for extra practice:

Key= /ɪ/ short and /iː/ long

a) When I feel the heat, I go to the beach.

b) Have you been to the beach this week?

c) Did you leave early to get some sleep?

d) He’s done a good deed. He fixed the leak in the sink.

e) Don’t steal, not even from the rich.

f) I like to eat a peach for a snack; first I peel it, then eat it.

g) I can’t play on the team until my feet are healed.

h) Leave the sheep to sleep for a week.

i) Jean, you must eat my green bean salad—it is delicious.

j) Tim and the team did leave before peak hour to reach the rich green field with ease in the heat.

You can do it! All you need is awareness and practice.

Are there any other English sounds you are wrestling with?

Request a free 20-second takeaway. Please contact me. I will post one for you.

* P. Ladefoged, Vowels and Consonants, Blackwell Publishing, Los Angeles, 2005, p.31

† L. Costamanga, Pronunciare l’italiano, Guerra Edizioni, Perugia, 1996

‡ Ladefoged, pp.26, 30

§ M. Garcia Bayonas, ‘Perception of English vowels as first and second language’, Revista Electronica de Linguistica Aplicada, no. 7, 2008, p.85

¶ Garcia Bayonas, p.79

** Ladefoged, p.122

†† Ladefoged, p.122

‡‡ D. Odden, Introducing Phonology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005, p.21

§§ Garcia Bayonas, pp.80, 86